How to level up your Architecture Career with Computational Design

Table of Contents

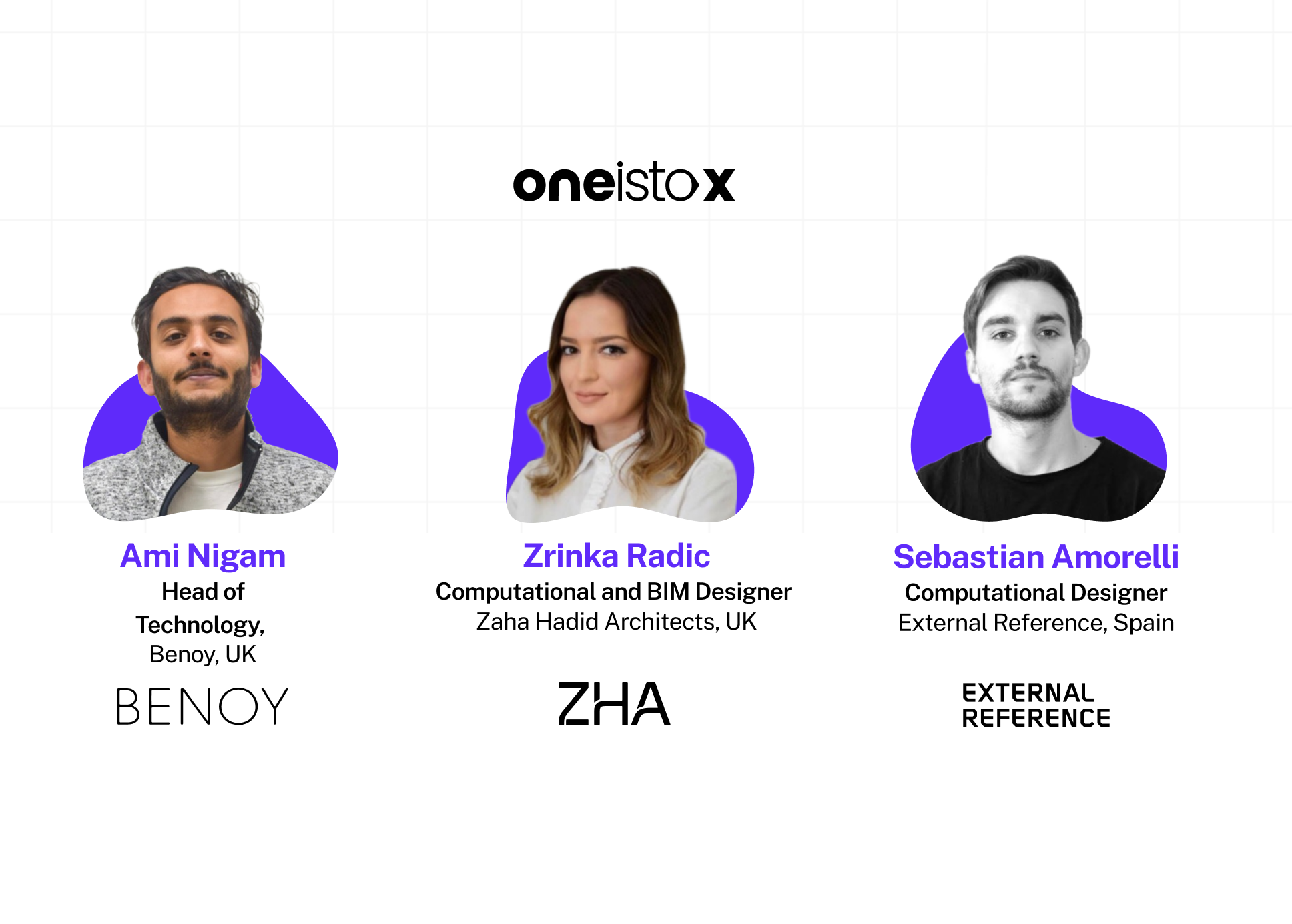

Computational Design is driving the future of architecture, transforming the way architects conceptualise, design, and construct buildings. Join us for an insightful discussion with industry experts—Ami Nigam, Head of Technology at Benoy, Zrinka Radic, Computational and BIM Specialist at Zaha Hadid Architects, and Sebastian Amorelli, Head of Computation at External Reference—as they share their experiences, insights, and advice on navigating a career fueled by Computational Design. Together, they will walk us through the impacts of Computational Design Architecture in the modern world.

Meet the Panelists

1. Ami Nigam

Ami Nigam is an architect and designer currently working as the Head of Technology at Benoy, UK. He has a Master's in Advanced Architecture from IAAC, Barcelona and is an expert in the verticals of BIM and Computational Design. He has ten years of experience under his belt, and he worked and lived in places like London, Hong Kong, Barcelona, Beijing, and Mumbai.

2. Zrinka Radic

Zrinka Radic, is a Croatian architect based in London. She holds a Bachelor's in Civil Engineering and she has also done her Master's in Advanced Architecture from IAAC, Barcelona. Zrinka currently works at Zaha Hadid Architects in London as a Computational and BIM Designer. Zrinka has worked on numerous projects varying in scale and complexity, working on competitions, concept design, schematic design, design development, to construction documentation as well. She has developed a strong work ethic in BIM workflow and project delivery methodologies. She also has a strong interest in combining the design methodologies associated with geometry, materiality, and fabrication.

3. Sebastian Amorelli

Sebastian Amorelli is an Italian architect, who graduated with honours from ORT University. He also holds a Masters in Advanced Architecture from IAAC, Barcelona. He's currently the Head of Computation at External Reference and a teacher of parametric design and interior designer at LCI Barcelona. He has a deep interest in Digital Fabrication and a professional specialisation in the development of complex geometries as well as parametric design. His research focuses on the development of parametric processes that are able to translate complex systems into design and fabrication techniques.

Q. Could you all tell us about some projects that you’ve been a part of that involved computational design?

Ami: I have two projects to talk about. One is from a very early point in my career, and one is more recent. Starting with a project called ‘Hive', which was developed by myself and two of my friends under a design collective called DeFacto. This is where we were taking our skills as architects outside of architecture - and seeing how we can use Computation and Digital Fabrication in a different context. This project is very special to me as it is one of my first projects in Grasshopper. At that time, I was a young and naive person with not many skills, but a lot of excitement about what was going on.

‘Hive’ by DeFacto – a project that Ami worked on

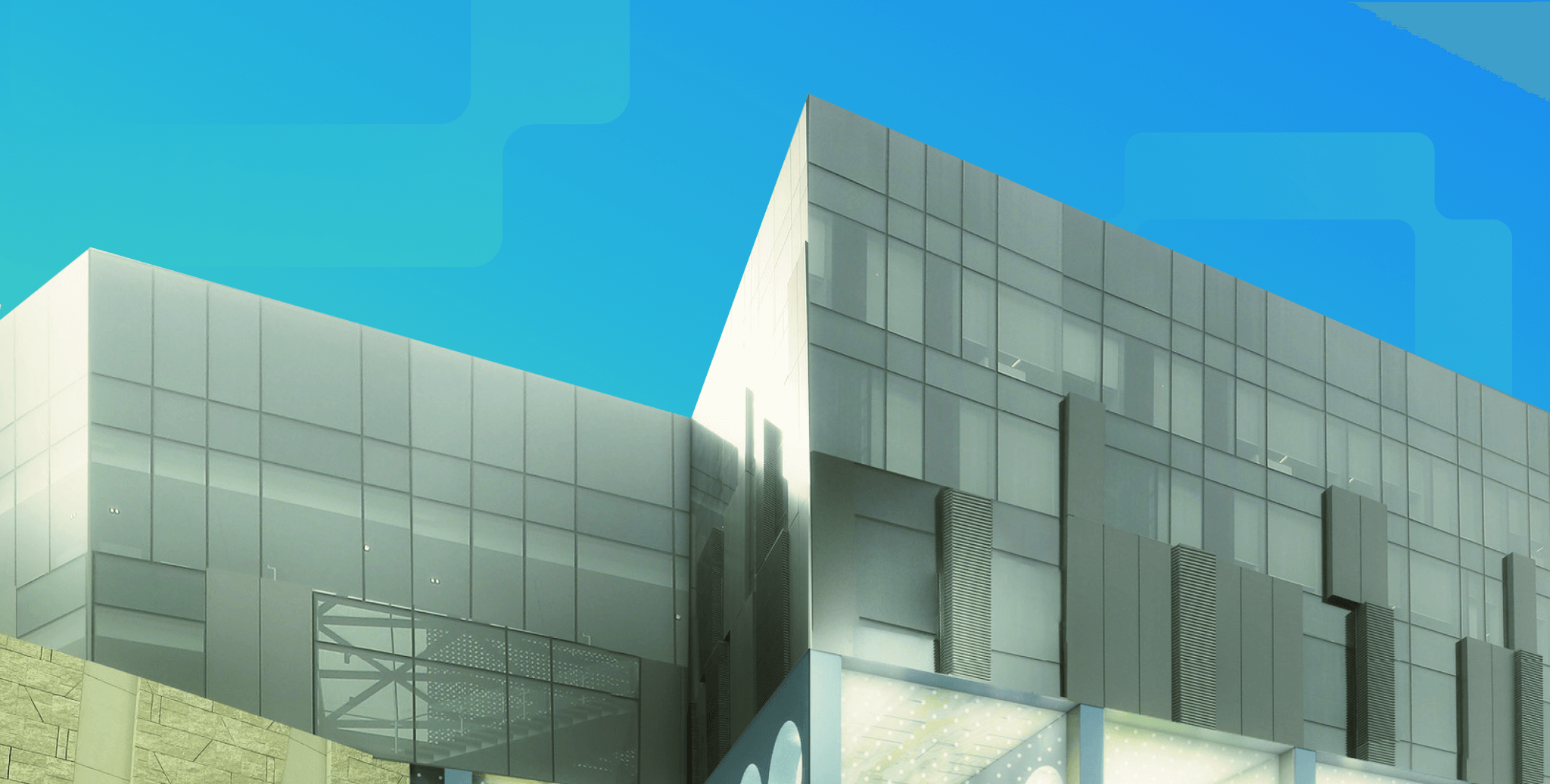

Ami: The second project was one I did at UNStudio – Tower C at Shenzhen Bay Super Headquarters Base. For this project, we were competing against Zaha Hadid Architects, BIG, KPF, and some of the big names! At first it was very daunting to me. I thought, how can I, with my background and skills, compete with the likes of Zaha? But it was a very rewarding experience, and I think it was the first time where I was understanding that now we're playing with the biggies. So, I think this is an interesting line between where I was very young, naive, knew very little, to where I developed more skills and was able to put them to use on massive projects of this scale..jpg?width=2000&height=1340&name=uns_superbayhq_dusk_op1_05.jpg(mediaclass-masthead-image.4e1a49d738a19641358911833dfb355bf10d147f).jpg)

‘Tower C at Shenzhen Bay Super Headquarters’ by UNStudio – a project that Ami worked on

Zrinka: A project that’s really close to my heart is the Rail Baltic Ülemiste terminal, Estonia. It is a new terminal, which is the starting point of a rail Baltic network that is going to connect with the European high speed train system. The terminal itself is designed as a public bridge that is going to be used by the local community, but also by all the commuters. This project, due to its scale and complexity, involves a lot of disciplines, and we've been using various computational design methods during the design stages.  ‘Rail Baltic Ülemiste terminal’ by Zaha Hadid Architects – a project that Zrinka worked on

‘Rail Baltic Ülemiste terminal’ by Zaha Hadid Architects – a project that Zrinka worked on

Sebastian: Among the projects that I led with External Reference was the Escaleras y Mirador Vela, a waterfront pavilion in Barcelona. This is a project that is very close to my heart as well, because it was the first opportunity we had to do a large scale project in Barcelona, the city that took me in. It was in a very iconic and beautiful place in the city. We had a very big challenge to fit this project in a very restrictive and existing setting. So, it was the first time I had the opportunity to really use the skills that I had acquired along my career.

We could also really experiment with what we're doing, thanks to our guidance, who really believed in us. So in this project, everything was done parametrically. There was a lot of testing and a lot of optimization. The whole concrete structure, the metal structure, the cladding, everything was designed using computational design tools. We could also use robotic fabrication to fabricate some of the panels, to make them bio-responsive, and to integrate native plants to add an extra layer to this.

‘Escaleras y Mirador Vela’ by External Reference – a project that Sebastian worked on

‘Escaleras y Mirador Vela’ by External Reference – a project that Sebastian worked on

Q. It’s interesting that you have all pursued Masters in Advanced Architecture from IAAC, Barcelona. At what point did each of you decide to study Computational Design? What influenced your decision?

Sebastian: What pushed me to pursue computation was quite a bit of frustration on my part after graduating. I didn't find that the job opportunities really catered to what I was expecting when I got into university. I also firmly believe that I didn't have the skill-set from university to go and work at firms that I admire, like Zaha Hadid Architects, Foster & Partners, and UN Studio. So, I started pursuing, I started doing my research, and I started to understand what I needed to know and what skills I needed to acquire to be able to do that. So, this is what pushed me to do my Masters.

Ami: I'd taken some time between my Bachelor’s and my Masters. After I finished my Bachelor's in the UK, I found myself in Beijing. And it was there, where I saw a lot of people use things like Rhino and Grasshopper. Over there, I was part of a small design collective with a few friends, and we were doing very avant-garde things - experimental 3D printing, the fashion piece you saw earlier, etc. At this point, I didn't know it was called computation, but I was really interested in 3D printing and Grasshopper. And what was really empowering to me was that you could write a piece of logic on a screen somewhere and materialise it and get something physical. That, to me, was revolutionary at that time.

So, I knew I was interested in this kind of technology. I looked for schools that were specifically looking at this. IAAC was one of the few places which was focused on this. They called it “bits to geographies”, which meant translating data into the built environment.

“I think it's quite important for us to have an intention with what we're trying to do with our careers. Find something that we like to do and then try to pursue it, instead of just going blindly and going through your Bachelor's, and then going through your Masters to get a job, which is not as exciting!”

Zrinka: I totally agree with Ami. I think you always need to have a goal, something you can't just be doing blindly. Even if your goal might change in the future, I think you should have a goal. How I got into computational design, I think, my story is quite different. I have a background in engineering, and even before university, I always had an interest in maths, physics, and computer science. I was never really a humanities person. Those subjects didn't really interest me. But during my time in engineering, I was really curious about the synergies between structural design, geometry, and architecture.

During my studies, unfortunately, I found out that I wasn't really getting this knowledge that I was expecting. I also realised that the disciplines are often very disconnected, one from another, which was quite surprising for me, and also very disappointing. So, I really wanted to understand how we can combine these fields. I just wanted to learn and know everything about it.

At the time in Croatia, none of my friends really knew about Computational Design. So, I was trying to search online and apply for a couple of Masters, but in the end I chose IAAC because it really caught my eye. They were focusing on interdisciplinarity, computational design, and digital publication. It was IAAC where I got introduced to Computational Design. The course was a bit overwhelming at first. Not because of the complexity of some topic, but it was just a lot of information that I was trying to process. But later, I really fell in love with it. It was a place to learn unconventional design approaches.

Q. Zrinka, your journey has been different because you come with a Bachelor’s in Civil Engineering. Could you tell us about your first architecture job and your first move into Computational Design?

Zrinka: So, my first job was back home with a family-run architecture and engineering firm, which was not that big. They were focusing on designing these traditional stone houses. They worked mostly on hotels and family homes. They worked a lot with conservation architects because these are usually projects in areas of protected heritage. It was a very nice office, but it was just my start. So, I was trying to learn how to use AutoCAD, drawing, and making mistakes with stairs. But it was a very nice environment. I think I did learn a lot from them. But yeah, it was totally different from the different kind of work that I do right now.

Q. When you were working in this organisation, did being a civil engineer make any difference in terms of work styles?

Zrinka: Well, not really. Actually, before my studies in IAAC, I also did an Undergraduate Course for a year in Architecture. Even during civil engineering, we had a lot of different topics in engineering, and the only ones that I actually liked were structural engineering. There were a lot of other engineering topics that I wasn't interested in at all. So, when I started working, I didn't really see a problem of not having this experience as an architect. I think I was self taught, in terms of general architecture. I was reading a lot more than other people because I didn't get this knowledge at first. So, it was quite hard to start. But I know a lot of architects that are very famous, who didn't even have a degree. I didn't see it as something that's going to stop me.

Q. Sebastian, did you start your career as a computational designer specialising in digital fabrication?

Sebastian: Digital fabrication came in when I got into IAAC. I went to do my Masters, actually wanting to pursue Computational Design and Parametric Design, but digital fabrication wasn't something that was in my mind at that time. But I picked it up in IAAC, and I was completely fascinated by it. To have all these new sets of tools that allow you to translate these complex and digital designs into the physical world, in a cost-effective and fast way.

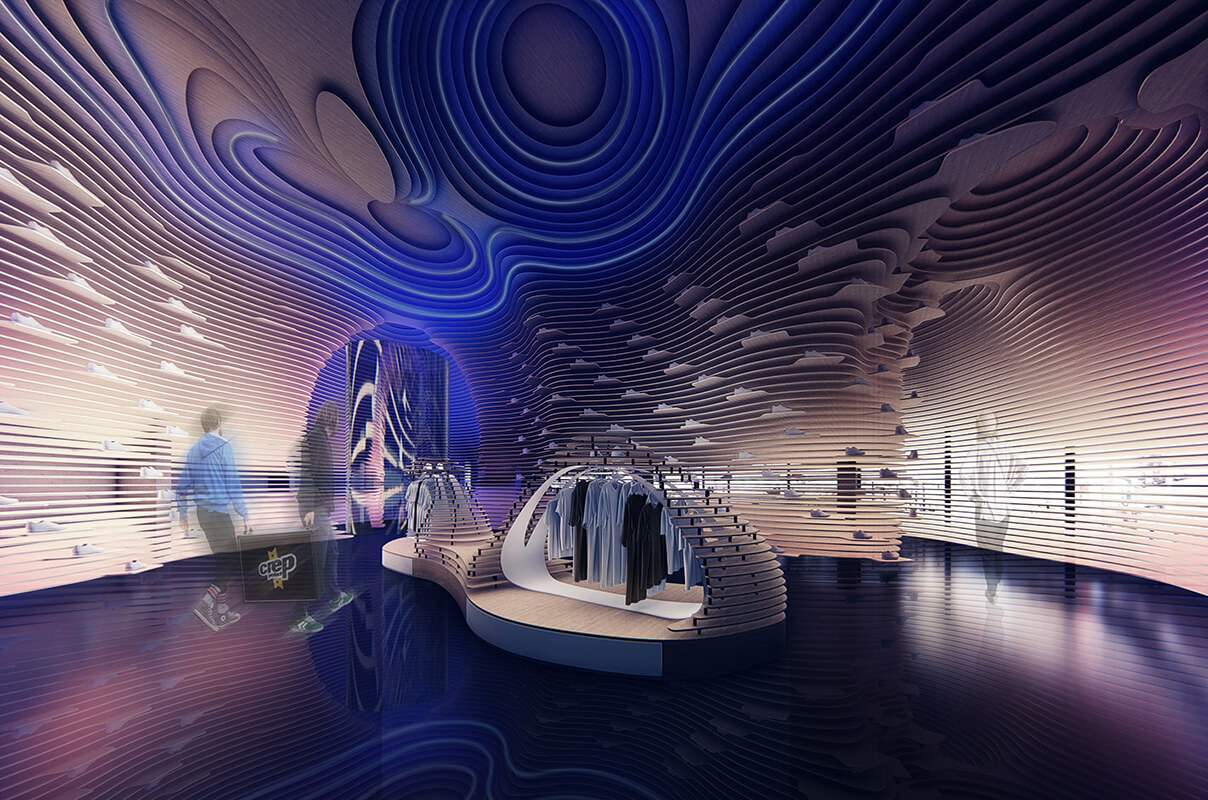

I was really lucky, because during my masters, I got invited to work with one of our tutors there, Carmelo Zappulla, the founder of External Reference. I joined this practice at the same time as I was doing my masters, and then I saw that at External Reference, they were really pushing Digital Fabrication, outside an academic setting. ‘Crep Protect Retail Store’, Dubai by External Reference – a digital fabrication project that Sebastian worked on

‘Crep Protect Retail Store’, Dubai by External Reference – a digital fabrication project that Sebastian worked on

We were trying to find a way to make our designs possible for clients in a timely fashion and in a cost-effective way. A lot of designs that we made, if they were not made by 3D printing, wouldn't be possible. For example, we did a store in Dubai that had 350 unique pieces that created the whole store. So how could we fabricate this project if we had to do 350 individual pieces in a cost-effective way and deliver the project in just four months? It wouldn't be possible. But with large-scale 3D printing, the translation from computer to the real world is very easy. We believe this is the future of construction.

Q. Ami, could you tell us what exactly ‘Design Technology’ means and how you specialised in it? How is your role as the Head of Design Technology different from that of a regular architect?

Ami: After IAAC, I found myself in Hong Kong working for a BIM consultancy as a Computational Designer. At the BIM consultancy, I was developing tools and workflows for Interoperability. And this is where the opportunity at UN Studio came about. They were looking for someone who was experienced with BIM. As I joined them, my role evolved more from an architect who can do technology to a technologist with a background in architecture.

This means that instead of traditional architects looking at one project, Design Technologists zoom out and their view is more studio focused. So, it was at UNStudio where my role evolved from an architect to a Design Technology Specialist. And now, my role is studio-focused rather than project-focused. This means that my teams are more concerned about the process of design rather than the product of design. How do we redesign the design process? How do we design and deliver fairly large, sophisticated projects, but also do data analytics? How do we do smarter coordination?

Visual programming, a major part of design technology in architecture firms

Visual programming, a major part of design technology in architecture firms

As a Design Technologist, I think the tools of your trade become slightly different. So, you're not working on a wall, a ceiling, or a canopy. You're working on scripts, families, and writing software. Fundamentally, you think more about the user experience, which means how are my teams going to pick up the tools that I've made and use it on projects?

How do we make tools that are very democratic? How do we empower our design teams with the right tools so that they're able to use combinations of the right tools to make their projects more meaningful? The tools of the trades are the same. We're still talking about Rhino, Grasshopper, Revit, Dynamo, Programming, and Sustainability. But instead of thinking how we use these tools on a project, we're thinking about how we create the tools using these softwares, that our design teams are going to be using.

So, fundamentally you're a little bit more zoomed out and you're trying to look at what is happening across different teams.

Q. Zrinka, could you also explain what your job role looks like? What’s the difference between being an architect and a Computational Designer?

Zrinka: So, I worked both as an architect and a Computational Designer. But, I didn't get the part that I am doing now overnight. It happened naturally and gradually. After studying Computational Design, Zaha Hadid Architects was a place where I really wanted to go, because they were always at the forefront of technology. And since the beginning, the office has always been a great driver in technological innovations and also one of the first to actually adopt the 3D digital design process.

So, I started there working as an architect, but I was using my computational design skills as an architect. But then over time, I realised that when you work on such complex projects, there are technical difficulties that occur that you need to solve as well. I got exposed to BIM. I tried to start applying my Computational skills and my BIM skills, and work at the intersection of both.

The main difference between an architect and Computational Designer is that an architect is someone who is trained to design and develop a project and needs to make sure that the design meets the requirements, code, and so on. They need to have technical knowledge. They need to know how to do the details to coordinate with the consultant clients. On the other hand, a Computational Designer is someone that is using computational tools to support the design. So whether you deal with BIM, geometry, sustainability, digital fabrication, you might develop different tools. And like Ami was mentioning, Computational Designers develop these scripts to support the project.

In my opinion, to be a good computational designer, you need to start working as an architect, because you need to have an understanding on why, when, and how you are using something. I think you need to have a generalist knowledge.

Q. What does it take for architects to secure jobs at established firms like Zaha Hadid Architects, UNStudio, and External Reference?

Zrinka: There are software skills that these offices require. So, software like Rhino, Grasshopper, Dynamo, these are a must. I think these are the most relevant tools that someone needs to have, when applying to these kinds of offices. If you don't have them, it's going to be really difficult to get a position. If you just use AutoCAD and SketchUp, it's not really going to get you into these offices because it's just not the tools that we use. I mean, we might sometimes use AutoCAD, but it's not enough. So these are the basic tools that you need. You don't have to be a super specialist at advanced tools, but you need to start and you need to be willing to learn.

Once you get the job, there are also other skills that you need to have. These are more soft skills, like your time management, coordination, and working with people. Because you might be the best coder or the best designer ever, but if you just work as one, it's going to be really hard.

Ami: I'm hiring right now and I'm looking at hundreds of portfolios every day. I think when I look at portfolios, I'm looking at it on three kinds of scales.

On the micro level, you need to know the skills of the trade. You need to have a documented skill-set throughout your portfolio. But, if you zoom out a little bit and you look at the macro, it's the ability to use these skills to come up with a comprehensive argument. So it's not good enough that you know how to do an attractive script. It's more important that you are tying the attractive script to a logic that is sustainable.

And then when you zoom out even more on a meso scale, it's about how the projects you've done weave a narrative about yourself. When I look at your portfolio, what does it tell me? What do you stand for?

“You need to be able to have a voice or a narrative about yourself. You need to know the skills. You need to be able to use those skills in the context of a project and have projects that speak to each other and tell me more about what you do. That would be a great portfolio.”

Q. Ami, could you tell us three things that you really look for in a portfolio?

Ami: First, documented skill set. It's not good enough that you say you have five stars on Grasshopper and four stars on Dynamo. I should be able to tell from your portfolio that you know how to use these skills.

Second is having an agenda, having a voice. The skills are good enough, but what are you doing with them? Do you care about sustainability? Are you more interested in computational fluid dynamics? Are you more interested in digital fabrication? How do you synthesise your skills into a product?

The most important thing is about having a narrative because when we're hiring people, we're looking for people who are going to work next to us, right? Skills can be learnt, but a narrative cannot be built. How you think about yourself, on a conceptual level, I think, is also very important. One of them was just emojis and talking about what their narrative is and how they are trying to build up a career in Design Technology. And as soon as I looked at that, I was like, okay, I want to know who this person is.

Q. How can architects take a step further to embrace the technology in overall design workflows? How can they display their narrative in their projects?

Ami: First, I think we have to be cognizant of the fact that technology is fundamentally changing the way we build and design the built environment. Everything from how a building is conceptualised to how it's coordinated and even built. As architects in today's age, we have to be aware.

For example, at Benoy, the way that we're approaching technology, we're looking for meaningful technology that helps us conceptualise a building, validate our design ideas, put a building together, help us communicate our designs better, and help us realise our vision. And at the same time, you're thinking about how we do this while streamlining efficiency, right?

There are opportunities to engage with technology at every process of design. If we're not doing that in today's age, then we're going to be extinct as architects. If we don't evolve, then as an industry, we're going to be replaced because engineers are doing a lot of the coordination.

As a student, I would say, look for opportunities in everything you do. Don't just think about the render and the drawing, think about how a project is being conceptualised. Then how do you validate those ideas and create a presentation that is cohesive, but is also very dynamic.

The tools are all around us and people around us are engaging with these things. So look for any ways to upskill that you can. Whether it's through structured learning, like Oneistox, reading papers, looking at conferences, education or skills. So, we need to be engaging with these things. It's not good enough today that you are doing CAD drawings and you have a nice render. Everything that happens before and after is as important, if not more.

Q. Zrinka, what, according to you, is the most important use of Computational Design?

Zrinka: I think it has a lot of uses. It allows us to explore a spectrum of design options and possibilities. It offers a lot of freedom to address either contextual or programmatic needs, to quickly evaluate the results and to find the designs that are embedded through data that we would be using. And it helps us make designs that are informed by data, be it fabrication techniques, structural performance or environmental performance. So, I think it gives us a lot of opportunity to explore the design itself and open doors to creatively fulfilling computational design jobs. Additionally, I think learning about this design practice also helps you bag a better Computational Design Architecture salary.

Another thing that I would say is very important is that it allows us to automate repetitive tasks and makes it easier to manage complex projects. It really reduces time and the risk of errors. In addition to this, it just allows much better collaboration between all the parties that are involved.

Q. Sebastian, what do you think is the future scope of Computational Design careers?

Sebastian: I think Zrinka touched on this topic very well. It can be applied to every part of the process. It's not that you have to use just one tool for design, construction purposes, or analysis. You just need to know how to use it.

In my case, we are very focused on the design part. So for us, Computational Design allows us to test a lot of design options and to be able to present them to the clients. Not one design option or solution. So, I believe it is the future in the AEC industry, but it just depends on how you specialise. You can be a Computational Designer, but I think you need to apply to one of the many fields across the AEC Industry because it's very broad.

Ami was also touching upon this and he’s focused now on developing tools for different teams. The same tools are not applied for design, analysis, geometry optimisation, or production optimisation. So, to be honest, I think in the future it will allow us to make the whole industry much more efficient, but at the same time much more creative.

Q. Any advice you’d like to offer to the next generation of architects and engineers?

Ami: So I always refer back to this concept. There's this very beautiful Japanese concept of ‘Ikigai’. Ikigai stands for the reason for being. If you can find something that you love, that the world needs, that you can be paid for, and you're good at, then it's your passion, it's your mission, it's your vocation, and your profession. That's where your life becomes truly meaningful.

Zrinka: Yeah, I really liked what Ami said. Find your niche. It might change, but have something you're trying to do. Stay curious. Embrace technology; it’s the only way we’re going to move forward as an industry.

Sebastian: Never stop looking. Be curious because the world moves very fast. So you need to catch up and look around. Don’t just look at the industry. We look a lot into the art world, into biology. There's a lot of things out there and there is nothing more beautiful than when you get a concept that is completely unrelated, completely out of the industry, and you manage to apply it to your own project or to your own career. That's, I think, when true innovation happens.

You can learn from Ami, Zrinka and Sebastian at Novatr’s Master Computational Design Course for Real-World Application.

- Become a Computational Design Specialist in just 10 months of part-time, online study.

- Learn from industry experts working at top firms like ZHA, Populous, and UNStudio.

- Master 6+ software, 15+ plugins and industry workflows.

- Build a core specialisation in High-Performance Building Analysis or Computational BIM Workflow.

- Get placement assistance to land your desired Computational Design Architecture jobs in globally operating firms.

Conclusion

Computational Design is becoming a vital avenue for architects to remain at the forefront of innovation as the architectural world changes dramatically. The insights shared by our industry experts underscore the profound impact Computational Design has on shaping the future of architecture. For aspiring architects and engineers, the key takeaways are clear: cultivate a niche, stay curious, and embrace technology as an integral part of the design workflow. Implementing Computational Design in your daily planning exercises helps you explore multiple horizons in architectural design. This ultimately will help you land more job opportunities and a better Computational Design Architecture salary in the industry.

If this sounds like something you would be interested in, check out our Master Computational Design Course to get ahead of the crowd.

Thanks for connecting!

Thanks for connecting!

-2.png)

-3.png?width=767&height=168&name=MCD%20B%20(Course%20Banner)-3.png)

/827x550/images/blog/blogHero/CG004_SC_WhatABIMSpecialistDoesAndHowToBecomeOne_0122_Image01.jpg)

.png)